What does “endangered” mean anyway?

“Endangered species” is a term most of us are familiar with. We know that endangered species need to be protected, that they are often threatened by human activities, and that we risk losing these plants and animals from our ecosystems. Around the world, more than 27,000 species are at risk of going extinct, but what does it really mean for a species to be “endangered” in Canada?

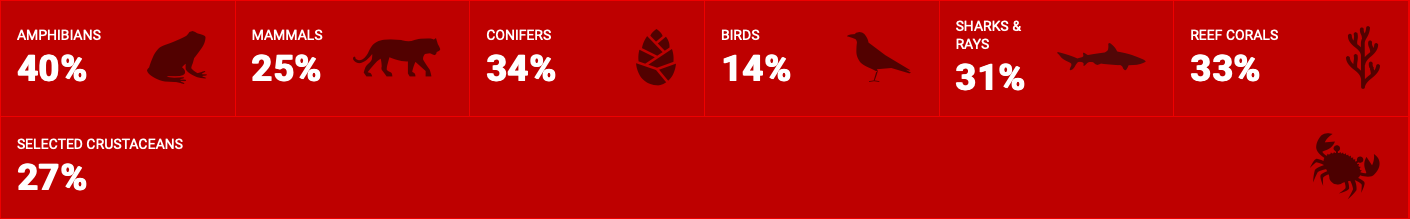

Global assessment of species threatened with extinction by organism group provided by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

What some of us might not know is that legal actions to protect these species are taken through Canada’s Species at Risk Act, often called “SARA”. Under SARA, a species can be listed as “extirpated”, “endangered”, “threatened”, or a “species of special concern”. Each of these categories means something a little different and changes the amount of protection given to a species.

Extirpated species no longer exist in one region of Canada, but they do exist in the wild in another area. Before the end of the 1800s, Atlantic Canada had its own population of grey whales. We know that this species existed here, but also that it doesn’t anymore, making the grey whale extirpated in Atlantic Canada.

Endangered species are those are that likely to become extirpated or extinct in the near future. These are the species that need our attention and fast action to protect habitat and eliminate threats. Our struggling friend the North Atlantic right whale has been listed as endangered under SARA since 2003 and the iconic piping plover has been listed as endangered since 2001.

Threatened species are those that are likely to become endangered if we don’t do anything to reduce or eliminate the threats that are impacting the population. New Brunswick’s own wood turtle has been listed as threatened under SARA since 2010, though was only listed as threatened under the New Brunswick Endangered Species Act in 2013.

Here is where it gets more complicated (yes, more complicated). The final category of SARA is a “species of special concern”. Under this category, species are given much less protection than species that are listed as extirpated, endangered, or threatened.

Species of special concern are those that might become threatened or endangered in the future because of their biology, like what they eat or what they need for habitat, or because of human activities. Some species of special concern in our province include the harlequin duck and the monarch butterfly.

Extirpated, endangered, and threatened species are protected from being killed, harassed, harmed, or captured by humans, while species of special concern are not given this same insurance. Similarly, the most important habitats, called “critical habitat”, are protected for extirpated, endangered, and threatened species only. When a species is listed as extirpated, endangered, or threatened, SARA requires that the government creates a “recovery strategy”. This requirement is one of the most important aspects of SARA because it requires the government to make an action plan that will help the species population rebound back to a healthy number. The recovery strategy for the North Atlantic right whale has resulted in some important actions in New Brunswick, like the creation of a protocol for rescuing whales caught in fishing gear and the relocation of shipping lanes in the Bay of Fundy to reduce the number of whales struck by commercial ships [1].

As a piece of federal legislation, SARA is only able to protect species in federal lands and waters, which leaves some species in provincial land, freshwater, and coastal ecosystems exposed to threats. We all know that wildlife doesn’t pay attention to our human boundaries, so New Brunswick needs to work just as hard to ensure that species at risk are protected in our province and fast action is taken toward conservation.

SARA is designed to protect the plants and animals that need our help the most, but it is not as strong at protecting species that might need our help in the future as climate continues to breakdown and ecosystems shift. This is why it is so important to protect all sorts of habitats that are home to all sorts of species: we need to ensure that all New Brunswick wildlife have what they need to survive and thrive in an unknown future.

CPAWS-NB is working tirelessly to support action from our governments to see the creation of protected area networks on land and at sea. These networks can help species at risk in all SARA categories by reducing threats from human activities and ensuring healthy habitat now and into the future. But to reach this goal, we need your help! By speaking up for nature and telling our governments that we need protected areas, we can help to protect New Brunswick’s wildlife and the ecosystems that make our province special.

If you’re worried about the North Atlantic right whale like many Canadians, take action with our friends at the Sierra Club Canada Foundation in an emergency letter-writing campaign here.

Header photo: “Piping Plover” by GregTheBusker is licensed under CC BY 2.0

References

[1] Brown, M.W., Fenton, D., Smedbol, K., Merriman, C., Robichaud-Leblanc, K., and Conway, J.D. 2009. Recovery Strategy for the North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis) in Atlantic Canadian Waters [Final]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada. vi + 66p.

Julie Reimer is a PhD student at the Memorial University of Newfoundland and a Board Member of CPAWS-NB. Having worked in the whale watching industry in New Brunswick and conducted her Master’s research on conservation planning for the North Atlantic right whale, Julie is an advocate for MPAs in New Brunswick. Julie’s current research attempts to see the “bigger picture” of conservation, reaching beyond protected areas to understand the synergies between conservation actions and ocean industries. To connect with Julie, visit http://juliereimer.wixsite.com/hello.